A Voice for the City

On the air at WTOP or in person, Mark Plotkin, BA '69, advocates for D.C. and more.

Mark Plotkin has stories.

There are stories about Washington's Marion Barry and about Chicago's Mayors Daley, Richard J. and Richard M.; stories about voting rights struggles in the District of Columbia; stories about graduating from George Washington University on "the five-year plan."

A political analyst and commentator for Washington's WTOP Radio and a fixture on the D.C. political scene for decades, Mr. Plotkin rolls out stories about growing up on Chicago's South Shore, about teaching in public schools in Washington and Chicago, and about his two failed runs for D.C. City Council in the 1980s.

Stories spill out of him like voting results on election night. There are tales about the long-forgotten campaign of former Pennsylvania Gov. Milton Shapp, about teaching tennis in Maryland's Montgomery County, about his long history with current Washington, D.C., Mayor and fellow GW alum Vincent C. Gray, BS '64.

Even Mr. Plotkin's collegiate memories tend to involve campaigns and contentious issues.

As an undergraduate living the GW dorm life in Foggy Bottom in the 1960s, he journeyed across the Potomac River to Fort Myer, Va., to watch the Colonials play basketball.

"It's a military base," he says. "You'd get all the way over there to the gate and then have to explain why you were there. And the gym. It was like playing in the Luray Caverns."

At the time, student Mr. Plotkin could not fathom why GW was a member of the South Carolina-based Southern Athletic Conference and had been since 1936.

"We were playing the Citadel and Furman and these schools in the Carolinas, and I couldn't understand why we were looking South rather than North and East," he says.

"Where were the [GW] students coming from? I thought we should be playing schools in New York and Philadelphia."

For most students, athletic conference membership is a conversation over a beer or a letter to the school paper. For Mr. Plotkin it was an early window into the kind of indefatigable activism that would come to define him.

"I want people to contend with me and with my ideas," he says. "I believe you should act. And I want to win."

Not for the last time, there was a committee, a campaign, a meeting with university officals. GW ended its participation in the Southern Conference in 1970. Never a slave to false modesty, Mr. Plotkin allows, "I didn't do it all myself."

Mr. Plotkin graduated from GW in 1969 with a degree in American history. But after more than four decades in Washington, his ties to his native Chicago are never far from the surface, particularly when the topic turns to politics, as it generally does.

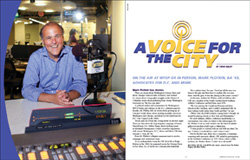

Mark Plotkin, BA '69, at the WTOP radio studios, where he hosts The Politics Program with Mark Plotkin.

Jessica McConnell Burt

Over lunch near the GW campus, he quotes baseball legend Bill Veeck, former federal Judge Abner Mikva, and an array of reputed Chicago crime bosses whose relatives managed to become city aldermen.

"In Chicago, all crime bosses are 'reputed,'" he says with a smile. "That means, you know, they're crime bosses."

His career inspiration, not surprisingly, is drawn from Chicago. Mr. Plotkin grew up listening to Len O'Connor, a celebrated radio and TV commentator revered by many in the city's reform circles.

"Len O'Connor was a guy I heard on the radio and TV in Chicago when I was growing up," he says. "He was fearless, and people listened to him."

In 1964 Mr. Plotkin was on his way to the University of Illinois at Champaign-Urbana, he says, when he came away with the impression that "it was a factory." Washington held a fascination, and he wanted to "get out of the Midwest."

On his self-described "five-year plan," Mr. Plotkin played on the tennis team and studied history and political science, sharing a house on 22nd Street for a time with Michael Weisskopf, a friend from the University of Chicago Laboratory High School, and later a correspondent for Time magazine.

Chicago was never far from his mind. In the summer of 1968, he went home to take in the tumultuous Democratic National Convention. He managed to acquire a job as a security guard inside the convention hall, watching over the well-being of CBS anchor Walter Cronkite.

After graduation, he gravitated toward teaching for a couple of years, first in Chicago and then in D.C. at River Terrace Elementary in Northeast and later at Moten Elementary in Southeast.

And he kept extremely busy on the presidential front, working on a quadrennial basis for Rep. Morris Udall, Sen. Edmund Muskie, Sen. Eugene McCarthy, Sen. George McGovern, Sen. Edward M. Kennedy, and Sen. Gary Hart.

It seems Mr. Plotkin labored as an advance man, congressional district organizer, and/or fundraiser for just about everyone in the Democratic Party with White House ambitions but President Jimmy Carter.

"We started D.C. Voters for Ted Kennedy in 1980," he says. "Got a second telephone line in my apartment and just started doing fundraising."

The common thread for Mr. Plotkin is that, over time, he brought the same encyclopedic knowledge of the political history and lore of his adopted city that he took from Chicago.

Mr. Plotkin immersed himself in the fine points and the endless battles around D.C. statehood and home rule, in the District's financial struggles in the '90s, in the trials and travails of former Mayor Marion Barry, and in the continuing effort to earn real congressional voting rights for the District. Along the way, he became a player in the politics of Maryland and Virginia as well.

In 1982, Mr. Plotkin found his niche in radio on WAMU, the NPR affiliate station in D.C. For a decade he shared the microphone with Mike Cuthbert, then with Derek McGinty, now a local TV anchor, and then with Kojo Nnamdi, who hosts a pair of public affairs radio programs on WAMU and WHUT.

"Mark invented himself," Mr. Nnamdi says. "He came to the station with this idea for a program about D.C. politics without much of a reputation and without much broadcast background. But he made it happen."

That same year Mr. Plotkin ran for D.C. City Council in leafy Ward 3, not faring well at the ballot box. Keeping busy, he wrote a regular column on D.C. political matters for the Legal Times.

In 2002, he moved to WTOP, the most listened-to radio station in the market. There he hosts The Politics Program with Mark Plotkin and offers running drive-time commentary on a range of issues, from mayoral antics to the odds that Virginia Gov. Bob McDonnell could wind up as a Republican vice presidential candidate in 2012.

He delivers analysis on WTTG Channel 5, the Fox affiliate in Washington, is a regular contributor to CTV in Canada, and also contributes to the BBC.

Mr. Plotkin earned the prestigious Edward R. Murrow Award for excellence in writing for commentary and an audience among Washington's political class. The New York Times' Francis Clines has described him as someone "who knows this city, rich and poor, better than any of the talking heads in the Sunday TV ghetto."

PBS analyst Mark Shields describes himself as "a fan and a regular listener" to The Politics Program as well as an occasional guest. They first met, he says, on the 1976 Mo Udall presidential campaign.

"Rarely these days do you find someone who is so passionate about what he does and believes in what he does and who is very good at it," says Mr. Shields.

"Mark holds everybody accountable, and around here he performs what I think is a singular public service, particularly looking at the District government."

In 1986, Mr. Plotkin made another stab at elected office, running again for City Council. It was his last race, though he still revels in the endorsement from The Washington Post and the fact that he came within 300 votes of a victory.

"I ran out of concession speeches," he says of drawing the curtain on his electoral ambitions. He insists, with typical fervor, that he did win an election, and re-election, to the D.C. Democratic State Committee in the 1980s.

While his energy never seems to lag, Mr. Plotkin is hard on the political culture he tracks. Politics in D.C. "has no character, no pizzazz, no flair," he says.

"Here [local politicians] get points for trying. It's not like Chicago, where outcomes are expected. There is a fascination with process rather than with results. Everyone just wants to fit in."

Despite his influential role in local and regional politics, Mr. Plotkin lays no claim to objectivity and never has. He is not a reporter, though he has broken more than his share of stories. He has been described variously as a "radio columnist" and "an odd medley of journalist and politician."

"Political advocacy is what Mark lives for," Mr. Nnamdi says. "It's what he wakes up for every morning.

"There is some Don Quixote in him. I really believe that if it were not for Mark's tireless advocacy for D.C. voting rights, for example, the whole question might be dead. He just won't let it die."

Once described by The Washington Post as "the motormouth champion of D.C. voting rights," Mr. Plotkin understands that his relentless style is not to everyone's liking.

"I'm seen by some people as confrontational or emotional or strident," he says. "All the adjectives."

None of that dissuades him. And campaign mentality, with a dose of Chicago bravado, has served him well in what is seen by many, even his critics, as his signature accomplishment.

In the late 1990s, the District was essentially in federal receivership and the John A. Wilson Building, the historic edifice at 1350 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W., that functions as City Hall, was in disrepair.

A deal was struck to turn the structure (formerly the District Building) over to developers. Simply put, the Environmental Protection Agency would occupy much of the historic space and the District government could settle for what was left.

Official Washington shrugged. The D.C. City Council sat back to absorb another indignity. The Washington Post evidenced little interest in the story.

Mr. Plotkin ramped up the outrage, even by his own considerable standard. The gadfly charges flew again and the call went out for Mr. Plotkin to let it go.

Then and now, Mr. Plotkin evoked his hometown on the matter.

"Can you imagine that going on in Chicago?" he squawks over lunch. "Somebody tells Mayor Daley they're going to take over City Hall? To be tenants in our own building? That would have lasted about a minute."

After what amounted to a three-year, one-radio-guy media campaign, Mr. Plotkin persuaded Jack Evans, a City Council member, to write a letter, signed by all his colleagues, to President Clinton.

Suddenly, Mr. Plotkin began piling up the points. In time, then-EPA Administrator Carol Browner made it known she had no interest in occupying the Wilson Building and called Mr. Plotkin to tell him so.

When it was over and this municipality of 600,000 souls had its City Hall back, they hung a picture of Mr. Plotkin, among others, outside the building, which did not bother him at all.

These days Mr. Plotkin is talking about President Barack Obama. In June, Mr. Plotkin told The Hill, a newspaper that circulates largely in Congress, that he would like to see a Democrat oppose the president in a 2012 primary.

Mr. Obama, he says, has done nothing to advance the cause of D.C. voting rights in Congress despite campaign pledges. And as part of a budget deal with Republicans, Mr. Obama supported a provision that barred the city from spending government money, even local funds, for abortion services. Mayor Gray and several council members were arrested for protesting the budget deal.

Confronted with the argument that his idea has no electoral legs in an overwhelmingly Democratic city that gave Mr. Obama 93 percent of its vote in 2008, Mr. Plotkin pushes back.

"I don't accept that," he says. "Don't see it that way at all. The president has taken the city for granted."

And another campaign begins.

Steve Daley is a Washington writer and communications consultant. He is a former columnist and national political correspondent for the Chicago Tribune.