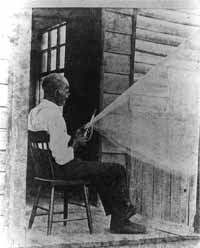

Former slave from coastal Georgia making a

fishing net, early twentieth century

Former slave from coastal Georgia making a

fishing net, early twentieth century(Collection of the Georgia Historical Society)

![[Previous]](images/prev.gif)

![[Next]](images/next.gif)

Former slave from coastal Georgia making a

fishing net, early twentieth century

Former slave from coastal Georgia making a

fishing net, early twentieth century

(Collection of the Georgia Historical Society)

My father was a carpenter and old massa let him have lumber and he made he own furniture out of dressed lumber and make a box to put clothes in. And he used to make spinning wheels and parts of looms. He was a very valuable man.

-- Carey Davenport, former slave from Walker County, Texas

Slaves had many noteworthy skills and talents which made plantations economically self-sufficient. The services of slave blacksmiths, carpenters, coopers, shoemakers, tanners, spinners, weavers and other artisans were all used to keep plantations running smoothly, efficiently, and with little added expense to the owners. These same abilities were also used to improve conditions in the quarters so that slaves developed not only a spirit of self-reliance but experienced a measure of autonomy. These skills, when added to other talents for cooking, quilting, weaving, medicine, music, song, dance, and storytelling, instilled in slaves the sense that, as a group, they were not only competent but gifted. Slaves used their talents to deflect some of the daily assaults of bondage. They saw themselves then as strong, valuable people who were unjustly held against their will rather than as the perpetually dependent children or immoral scoundrels described by so many of their owners. Indeed, they found through their artistry some moments of happiness, particularly by telling tales which portrayed work in humorous terms or when singing satirical songs which lampooned their owners.

Richard Toler, former slave from Campbell

County, Virginia (20.1)

Richard Toler, former slave from Campbell

County, Virginia (20.1)Richard Toler was trained as a blacksmith during slavery and later went on to try his hand as a carpenter and stonemason. He could also play the fiddle but recalled that he and his people were always treated poorly on the plantation:

"The dog was superior to us. They would take him in the house . . . ."

When I was about twelve, I help Daddy Patty in his tanning yard over there on the water by the cemetery. Patty was a shoemaker too and used to make all kinds of things out of hides and skins.

-- Henry Williams, former slave at Oakland plantation in Camden County, Georgia

My old Mistis promise me

Dat when she died, she gwine set me free.

But she lived so long and got so po'

Dat she lef me diggin' wid er garden ho'.

-- plantation song recalled by Abram Harris, former slave from near Greenville, South Carolina

Lucindy Jurdon, former slave from Georgia

(21.2)

Lucindy Jurdon, former slave from Georgia

(21.2)Lucindy Jurdon reported to her interviewers:

"My mammy was a fine weaver and she work for both white and colored [people]. This is her spinning wheel, and it can still be used. I use it sometimes now."

Unknown banjo player from near Savannah,

Georgia (21.3)

Unknown banjo player from near Savannah,

Georgia (21.3)The banjo was commonly played by slaves in the quarters. African in origin, the instrument provided simultaneously both a melodic and a percussive accompaniment for improvised verses. Under the guise of humor, slave musicians criticized and mocked the planter class.

Gathered around the hearth in the evenings, slave elders told folktales intended both to entertain and to educate. Tales with animal characters were favored but it was clear to all that these narratives contained important lessons about human conduct.

A Tall Tale about Tall CornOne day I was walking past a forty-acre patch of corn, on the Governor Heywood plantation by the Combahee River, and the corn was so high and thick, I decide to ramble through it. About halfway over, I hears a commotion. I walks on and peeps. There stands a four-ox wagon backed up to the edge of the fields, and two men was sawing down a stalk. Finally they drag it on the wagon and drive off. I seen one of them, in a day or two, and asks about it. He say: "We shelled 356 bushels of corn from that one ear, and then we saw 800 feet of lumber from the cob."

-- told by John Henry Smith of Little Rock, Arkansas, son of former slaves from South Carolina, and attributed to his father

Katie Brown had a reputation as a fine storyteller. One of her favorites was the tale about a magic sword which would work by itself if the correct password was given. Those who tried to use it without knowing the proper commands suffered dire consequences.

Next section of The Cultural Landscape of the Plantation Exhibition

Table of contents for The Cultural Landscape of the Plantation Exhibition