|

Related posting

The

Creation of SIOP-62

More Evidence on the Origins of Overkill

More

Archive postings on nuclear history

|

|

Secretary

of Defense Melvin Laird and Director of Defense Research and

Engineering John S. Foster, former chairman of the National

Strategic Targeting and Attack Panel, at a Pentagon surprise

reception in honor of Foster, 2 October 1972 (Photo, courtesy

Office of Secretary of Defense Historical Office) - larger

version |

Washington, D.C., November 23, 2005 - The nuclear war plans

that constitute the Single Integrated Operational Plan have been among

the most closely guarded secrets in the U.S. government. The handful

of substantive documents on the first SIOP -- SIOP-62 (for fiscal

year 1962) -- that have been the source of knowledge about it have

been declassified, reclassified, re-released, and then closed again,

fortunately not before key items had been copied at the archives.

(Note 2) More about the SIOP remains unknown than

known to the public and important details such as targets systems,

weapons assignments, and bomber and missile routes have remained top

secret for years and may remain so indefinitely. Federal agencies

routinely deny large portions of documents with information on the

SIOP. Nevertheless, significant information about U.S. nuclear war

plans as they evolved through the late 1960s and early 1970s has been

declassified through FOIA requests, mandatory reviews at the National

Archives, and routine declassification. With this briefing book, the

National Security Archive publishes for the first time recently declassified

documents on nuclear war planning during the years of the Nixon presidency.

Declassified documents show what the SIOP had become during the

Nixon administration. Originally a plan for a single massive nuclear

strike launched either preemptively or in retaliation against the

Soviet Union and the Soviet bloc (Note 3), under

the influence of the Kennedy administration the SIOP became a set

of plans with five major options for nuclear strikes. Preemption

was always an option but preemptive attacks depended on the availability

of strategic warning intelligence showing that a Soviet attack on

the United States was imminent. If, however, the U.S. authorities

had tactical warning information, e.g. the 15 minutes provided by

Ballistic Missile Early Warning System (BMEWS) radars, showing that

the Soviets had already launched missiles, they could order retaliatory

strikes.

The National Strategic Targeting and Attack Policy (NSTAP), approved

by the Secretary of Defense and the Joint Chiefs of Staff, guided

the preparation of the SIOP. Influenced by the "counterforce"

thinking of the early 1960s, it sought to spare, or at least minimize,

civilian casualties from some of the attacks by avoiding cities

and focusing on the adversary's nuclear weapons capabilities. (Note

4) The NSTAP established three core tasks, the chief of which

was the destruction of nuclear threat targets:

- ALPHA: to destroy Soviet and Chinese strategic nuclear delivery

capabilities located outside of urban areas. This task included

the destruction of high-level Chinese and Soviet military and

political control centers.

- BRAVO: to destroy non-nuclear Soviet and Chinese conventional

military capability (including barracks, tactical air fields,

and the like) located outside of urban areas.

- CHARLIE: to destroy Chinese and Soviet nuclear weapons capabilities

located in urban areas, as well as 70 percent of the urban-industrial

sector.

Following the NSTAP, the SIOP provided the National Command Authority

(the President and Secretary of Defense,) with five attack options

against the Soviet Union and other communist countries:

- a preemptive strike against ALPHA target categories. In 1971,

this strike required some 3200 bombs and missile warheads (including

multiple independently retargetable reentry vehicles or MIRVs)

to destroy 1700 installations.

- a preemptive strike against ALPHA and BRAVO target categories.

In 1971, this strike required some 3500 programmed weapons to

destroy 2200 installations.

- a preemptive strike against ALPHA, BRAVO and CHARLIE target

categories. In 1971 this would have involved some 4200 programmed

weapons targeting 6500 installations (some of which were adjacent

or "co-located").

- a retaliatory strike against ALPHA, BRAVO, and CHARLIE target

categories; in 1971 this required some 4000 programmed weapons

targeting 6400 installations (some of which were co-located).

- a retaliatory strike against ALPHA and BRAVO target categories.

In 1971, the exercise of this option required 3200 programmed

weapons to destroy 2100 installations.

Besides the attack options, the SIOP included "withholds"

for excluding attacks on some targets. For example, attacks on major

command and control installations in Moscow and Beijing could be

withheld if U.S. command authorities wanted to preserve lines of

communication with the Soviet Union or China. Attacks on entire

countries, e.g. China, Poland, or Romania, could also be withheld

if they were not in the war or for other political or military reasons.

Some 600 weapons were slated for a maximal attack on Chinese military

and urban-industrial targets.

|

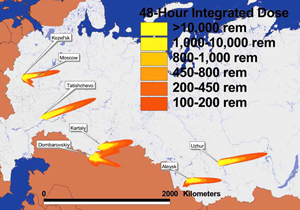

Fallout

Patterns from an Attack, Consistent with the ALPHA Task of

the National Strategic Target and Attack Policy, on All Active

Russian ICBM Silos - larger

version |

Just like senior national security officials in the current Bush

administration, who seek to make nuclear weapons more useable by

assigning them bunker-busting missions, the Nixon Administration

wanted to be able to construct nuclear threats that were more credible

than the catastrophic SIOP options. During a visit to the Pentagon

in late January 1969, only days after the inauguration, Richard

Nixon and Henry Kissinger received their first SIOP briefing; they

were startled by what they heard in part because they found the

attack options to be unbelievable and unusable for East-West crises

in Europe, the Middle East, or Asia. Previous presidential administrations

had promoted the idea of a wider, more discriminating, range of

nuclear options and the RAND Corporation and the Air Force were

analyzing the possibility through the NU-OPTS studies. Believing

that the president should have military options other than an unbelievable

threat of massive nuclear attacks, Kissinger began pushing the national

security bureaucracy to come up with ideas and plans for the more

selective use of nuclear weapons that would be more useful for political

threat purposes and even for actual military use. During the months

that followed, White House pressure on the bureaucracy produced

scant results, although eventually the Pentagon became more responsive

to Nixon's and Kissinger's interest in strategic alternatives.

From 1972 to 1974 an internal Pentagon study laid the way for an

interagency study that presented the rationale for escalation control

and selective nuclear targeting. Although some voices inside the

government raised doubts about the possibility of controlling nuclear

escalation, Kissinger brushed them aside. By early 1974, President

Nixon signed a national security decision memorandum directing the

preparation of a "wide range of limited nuclear employment

options" that could be used to demonstrate the seriousness

of the situation to an adversary as well as show a "desire

to exercise restraint." This briefing book also includes documents

on Nixon-era planning to make nuclear weapons more useful politically

and militarily.

Before Nixon signed the NSDM (see document 24A below), Secretary

of Defense James Schlesinger, with whom Kissinger had a competitive

working relationship, made informal remarks to the press that disclosed

some of the features of the new selective targeting policy with

his own spin emphasizing the importance of counterforce. Schlesinger's

remarks received considerable press coverage and became the subject

of much comment, some highly critical, in Washington, Moscow, and

Western Europe. The new approach was quickly dubbed, no doubt to

Kissinger's dismay, the "Schlesinger Doctrine." (Note

5) During the months that followed, the Pentagon initiated a

complex, and not altogether successful, effort to meet the demands

of its political masters for a range of nuclear options responsive

to presidential wishes. (Note 6)

A recently published article by the editor of this compilation

provides more information on the SIOP as it stood during the Nixon

administration and the White House's search for limited nuclear

options; see William Burr, "The

Nixon Administration, the 'Horror Strategy,' and the Search for

Limited Nuclear Options, 1969-72: Prelude to the Schlesinger Doctrine,"

in the summer 2005 issue of The Journal of Cold War Studies.

More information on SIOP reform during 1972-1976 appears in William

Burr, "'Is This the Best They Can Do?,' Henry Kissinger and

the Quest for Limited Nuclear Options, 1969-1975," from Vojtech

Mastny, Andreas Wegner, and Sven S. Holtsmark, eds., War Plans

and Alliances in the Cold War (London: Routledge, 2006). Both

articles draw on archival records and other declassified material,

some of which appears below.

Documents

Note: The following documents are in PDF format.

You will need to download and install the free Adobe

Acrobat Reader to view. I.

SIOP-4

Document

1: "Joint Staff Briefing of the Single Integrated Operational

Plan (SIOP)," 27 January 1969, Top Secret, excised copy

Source: FOIA release by U.S. Air Force

On January 27, 1969 President Nixon lunched at the Pentagon

with Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird and then received a briefing

at the National Military Command Center. Prepared by Colonel Don

LaMoine of the Joint Staff, this is the text for the briefing

on the latest version of the war plan, SIOP-4, as prepared by

the Joint Strategic Target Planning Staff (JSTPS) under the supervision

of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the Secretary of Defense. SIOP-4

was a revision of SIOP-64, which was in turn an update of SIOP-63.

The basic options remained the same; SIOP-63 set the mould for

U.S. nuclear war plans through the mid-1970s. The Air Force has

withheld key portions of this briefing but documents 2 and 3 which

follow provide information on some of the major excised portions,

such as the discussion of the NSTAP and the SIOP options.

Document

2: National Security Council Staff, "Strategic Policy

Issues," circa February 1, 1969, Top Secret, excerpt

Source: National Archives, Nixon Presidential

Materials Project (NPMP), Henry A. Kissinger Office Files, box

3, folder: Strategic Policy Issues

This staff study includes some useful figures: numbers of strategic

nuclear forces, including missile warheads, on both sides as well

as estimates of fatalities caused by a nuclear exchange. For example,

in response to "highest threat"--a Soviet first strike--U.S.

forces could still "inflict 40% Soviet fatalities (90 million)

through the early to mid-1970s." The fatality rates caused

by a preemptive attack on all target categories would have been

higher but such estimates remain classified. (Note

7)

Document

3: Laurence E. Lynn, Jr. to Dr. Kissinger, "The SIOP,"

8 November 1969, Top Secret

Source: NPMP, NSC Files, box 384, folder: SIOP

(Single Integrated Operational Plan), mandatory review release

This memorandum by NSC staffer Lawrence E. Lynn, Jr., includes

invaluable information on the NSTAP and the SIOP options. Lynn's

memo was a response to requests from Henry Kissinger for concepts

of, and plans for, smaller, less destructive, strike options that

would enable the White House to make nuclear threats that were

supposedly more credible to an adversary than a catastrophically

massive SIOP strike. Lynn's attempt to develop the concept for

an alternative strike plan included a critique of a JCS report

prepared earlier in the year that argued that the SIOP was fine

as it was and that trying to change it would weaken the plan.

The JCS report, as transmitted with a memo from Secretary of Defense

Laird, is attached to Lynn's memo. Kissinger scrawled his puzzled

query to his military assistant, Colonel Alexander Haig--"What

does this mean?"--on the top of Laird's memo.

Document

4: National Security Council, Defense Program Review Committee,

"U.S. Strategic Objectives and Force Posture Executive Summary,"

3 January 197[2], Top Secret, excerpt

Source: Declassification release by NSC

Important detail on the NSTAP and the SIOP can be found in a

long report prepared during 1971 by an NSC subcommittee, the Defense

Program Review Committee, chaired by Henry Kissinger. The Committee

looked exhaustively at the U.S. military posture and budgets,

with a close look at the SIOP and the risks and benefits of developing

limited nuclear options (pages 45-56). The declassified report

includes significant information on the NSTAP and the SIOP, including

options and numbers of weapons and targeted installations (see

pages 27-28). Incorporated into the report was a critical assessment

of the SIOP that drew upon a major JCS study of the SIOP (see

document 15b below). According to the assessment U.S. strategic

forces "cannot destroy a significant part of the Soviet nuclear

delivery capability" which meant that they "cannot significantly

limit damage to the United States and its allies." Nonetheless,

U.S. nuclear forces could "inflict damage on 70% of the war-supporting

economic targets in the USSR and China." In addition, the

study provides additional estimates of "prompt" or immediate

fatalities (from blast, radiation, etc.) that would be caused

by a U.S. retaliatory attack on the Soviet Union (see page 18).

This study includes a detailed breakdown (page 35) of the nearly

13,000 tactical nuclear weapons stationed overseas, including

weapons deployed overseas, e.g., Western Europe, East Asia, and

"afloat" (storage ships, aircraft carriers, etc.). It

also includes a review of alternative nuclear strategies toward

China (see pages 99-108) with the pros and cons of a potential

"disarming strike" option geared toward destroying Chinese

strategic forces. Even though Kissinger had already made his secret

trip to China five months earlier and Sino-American rapprochement

was unfolding, the PRC remained a target for U.S. military planning

until the early 1980s. (Note 8)

Document

5: Haldeman Diary, Entry for 11 May 1969

Source: NPMP, Special Files, H.R. Haldeman Diary

Returning from a trip to Florida on May 11, 1969 President Nixon

flew back on the National Emergency Airborne Command Post (NEACP),

a Boeing 707 (or EC-135) which was designed for commanding military

forces during a crisis. There Nixon participated in a text exercise

which probably involved practicing the SIOP options. Nixon's chief

of staff H.R. Haldeman observed that "it was pretty scary."

Nixon "asked a lot of questions" especially about the

"kill results. Obviously worries about the lightly tossed

about millions of deaths."

II.

The Search for Limited Nuclear Options

Document

6: "Notes on NSC Meeting 13 February 1969," 14 February

1969, Top Secret

Source: NPMP, NSC Institutional Files (NSCIF),

box H-20, folder: NSC Meeting, Biafra, Strategic Policy Issues

2/145/69 (1 of 2)

This transcript of the discussion during a National Security

Council meeting does not go into the SIOP but it provides some

insight on strategic thinking early in the Nixon administration,

including recognition of the danger, and possibility, of launch-on-warning

and the weakness of U.S. nuclear guarantees to allies. Kissinger

also showed his interest in limited nuclear options by discussing

the possibility that the superpowers would avoid massive nuclear

attacks on each other by resorting to "smaller packages."

Document

7: NSC Review Group Meeting, "Review of U.S. Strategic

Posture," 28 May 1969, with Halperin memo attached, Top Secret

Source: NPMP, NSCIF, box H-111, folder: SRG Minutes

Originals 1969

When Nixon came to power and appointed Kissinger as his national

security assistant, the latter began issuing requests for studies

to the military and foreign policy bureaucracy, in part to get

a better grasp of key issues but also to keep the agencies absorbed

in this work so they would not interfere with White House decisions.

One of the requests, National Security Study Memorandum 3, asked

for a study of the U.S. military posture and the balance of power.

The NSC Review Group, an interagency committee chaired by Kissinger,

discussed the draft of the NSSM 3 study during a meeting in late

May 1969. About half-way into the meeting, the conversation turned

to the possibility that the Soviets might launch a limited, "discriminating,"

nuclear attack instead of a massive nuclear strike. Kissinger

implied that such an attack was possible because it was not rational

"to make a decision to kill 180 million people," but

R. Jack Smith, Deputy Director for Intelligence at CIA, argued

that a limited attack was the "least likely contingency -

one could not believe that the Soviets would launch a few nuclear

ICBMs against the US."

Document

8: Laurence E. Lynn, Jr. and Helmut Sonnenfeldt to Dr. Kissinger,

"June 18 NSC Meeting on U.S. Strategic Posture and SALT,"

June 17, 1969, memorandum to President Nixon, briefing materials

and reports attached, Top Secret

Source: declassification release by NSC

The response to NSSM 3 was slated for discussion at an NSC meeting

on June 18, 1969. The package of materials that the NSC staff

prepared for Nixon and Kissinger included some discussion of the

problem of discriminating nuclear strikes, now characterized as

"disarming attacks" or "less than all-out strikes"

on nuclear forces, partly as a means to improve the attacker's

"relative military position" but also as a way to bring

a war to a halt in order to avoid strikes on cities. Kissinger

and the NSC staff saw this "as the most sensible strategy

for us to consider under the extreme pressures of a nuclear crisis

or threat."

The reports also included criteria for "sufficiency"

that the Nixon White House would use as a yardstick for evaluating

the "adequacy of U.S. strategic forces" as well as the

suitability of strategic arms control agreements with the Soviets.

Coined by Henry Kissinger, the "sufficiency" concept

aimed at making the new administration's strategy look innovative

and moderate, deploying enough forces to deter without looking

inordinately aggressive.

Documents

9a and 9b: Requests for Studies

- Document

9a: Kissinger to the President, "Additional Studies

of the U.S. Strategic Posture," July 1, 1969, with Lynn

memo attached, Top Secret

Source: NPMP, NSCIF, box 56, folder:

NSSM-64

- Document

9b: National Security Study Memorandum 64, Kissinger to

Secretary of Defense, "U.S. Strategic Capabilities,"

July 8, 1969, Top Secret

Source: NSC Freedom of Information release

Kissinger's search for "more discriminating options than

the present SIOP," which would be appropriate for the "kinds

of situations which the President might actually face in a crisis,"

led to a request for Nixon's approval of a new National Security

Study Memorandum, NSSM 64. The request, which Kissinger signed

on July 8, 1969, did not explicitly mention the SIOP or "discriminating

options" but nonetheless tasked the Defense Department to

evaluate how well U.S. strategic forces would stand up to strategic

nuclear attacks in terms of their "capability to deter and

respond to less than all-out or disarming Soviet attacks"

as well as a "a range of possible war outcomes." Other

problems to be studied were force mixes, command-and-control improvements,

and possible changes in the criteria for strategic sufficiency.

Document

10: General Richard A. Yudkin, "The Changing Context,"

Address to Tactical Nuclear Weapons Symposium at Los Alamos National

Laboratory, 3 September 1969, with cover memos from Haig and Hughes

attached, Secret

Source: NPMP, NSC Files, box 818, folder: Hughes,

Col. James D., mandatory review release

During the late 1960s and early 1970s, the RAND Corporation and

the U.S. Air Force undertook a series of studies--"NU-OPTS"--on

the possibilities and potential of "selective nuclear operations"

as an alternative to the massive SIOP options. (Note

9) A key figure on the Air Force side was General Richard

Yudkin, whose Los Alamos speech gave a highly positive assessment

of NU-OPTS as an "additional option short of full-scale nuclear

attack [which] can make more politically credible our international

commitments which are not directly related to national survival."

While Yudkin acknowledged that once some nuclear weapons were

used, pressures for all-out attack-"executing the Assured

Destruction capability"-would increase on both sides, he

argued that those pressures "will not reach the same magnitude

as the pressures against" such an attack. "I believe

this resistance to the launching of Assured Destruction will hold

up on both sides-in the USSR as well as the U.S." NSC staffer

Alexander Haig was enthusiastic about NU-OPTS, although it is

unclear whether Kissinger learned about the studies or even if

Yudkin gave a briefing to top officials at the Pentagon. The NU-OPTS

work presaged, and possibly influenced, the Foster Panel's work

on limited nuclear options (see documents 16, 18, and 19), although

more needs to be learned about the relationships.

Document

11: L. Wainstein et al., The Evolution of U.S. Strategic

Command and Control and Warning, 1945-1972, Study S-467,

Institute for Defense Analyses, June 1975, Top Secret, excerpt

Source: FOIA release (document published in its

entirety in National Security Archive, U.S. Nuclear History:

Nuclear Weapons and Politics in the Missile Era, 1955-68

(Washington, D.C., 1998)

The study that the Pentagon prepared in response to NSSM 64 remains

classified, but an Institute for Defense Analyses history prepared

several years later summarized its "gloomy" conclusions

about the command and control requirements for conducting limited

strategic war. According to the NSSM 64 study, despite the U.S.'s

"good capability" to "execute a preplanned attack,"

its "Command Centers do not possess the combination of survivability

and capability which is required for the conduct of limited strategic

nuclear war." Neither the National Military Command Center

(NMCC) at the Pentagon nor the Alternative National Military Command

Center (ANMC) at Fort Ritchie, Maryland was survivable while the

NEACP had "limited capability." Those conclusions cast

cold water on the possibility of limited strategic options, but

how Kissinger reacted to them remains unknown.

Document

12: Cable from Commander-in-Chief Strategic Air Command Holloway

to JCS Chairman and Air Force Chief of Staff Ryan, "Visit

of Dr. Henry Kissinger to HQ SAC," 10 March 1970, Secret

Source: National Archives, Record Group 218, Records

of Joint Chiefs of Staff, Chairman Earl Wheeler Files, box 80,

folder: 323.3 CINCSAC, FOIA release

Wanting to learn more about the SIOP, Kissinger flew to Strategic

Air Command headquarters at Offutt Air Force Base in Nebraska,

where he received more briefings on the strategic threat and SIOP

options from the JSTPS. According to SAC's commander-in-chief

(CINCSAC) and JSTPS director General Bruce Holloway, the briefings

"were well received," with Kissinger showing interest

in the "flexibility" of SIOP options. Nevertheless,

some things Kissinger was not allowed to learn: "certain

aspects of the SIOP … were deliberately not gone into."

Document

13: Record of Telephone Conversation Between Henry Kissinger

and Under Secretary of State Elliot Richardson, 10 March 1970

2:25 p.m.

Source: NPMP, Henry A. Kissinger Telephone Conversation

Transcripts, box 4, March 10-16, 1970

The briefing might not have been received quite as well as Holloway

believed; a conversation that Kissinger had with Elliot Richardson

suggested his doubts. While the discussion is not entirely clear,

Kissinger appeared to have been skeptical about the "limited

options" involving an "enormous number of missiles"

and only a "few bombers." He also questioned SAC's identification

of the Soviet SA-5 surface-to-air missile as an anti-ballistic

missile: "I made them back up."

Document

14: "President's Review of Defense Posture San Clemente

July 28, 1970 [,] Selected Comments," Top Secret

Source: NPMP, NSCIF, box H-100, folder: DPRC Meeting

11-24-70

During a meeting on defense budgets at the Western White House,

Nixon and Kissinger discussed the roles and missions of the services

and the problem of cutting defense budgets. Nixon vented some

spleen about the military bureaucracy; both the Pentagon and the

Air Force had "unbelievable" layers of bureaucracy,

with the latter being especially "disgraceful" in that

respect. Predictably, Kissinger brought up the need to reform

the SIOP--the "horror strategy" as he characterized

it--but Nixon did not show much enthusiasm about ordering a study,

despite Kissinger's request.

Documents

15a-b: SIOP Analysis

Source: FOIA releases

- Document

15a: Memorandum from Secretary of Defense Laird to Chairman,

Joint Chiefs of Staff, "Analysis of the SIOP for the National

Security Council," August 15, 1970, Top Secret

- Document

15b: Joint Chiefs of Staff, "Analysis of the Single

Integrated Operational Plan for the National Security Council,"

April 23, 1971, Top Secret, excised copy

Whether Secretary of Defense Laird knew about Nixon and Kissinger's

discussion or not, only a few weeks later he commissioned a major

evaluation of the SIOP. Certainly, Laird understood that the White

House was not enthusiastic about the inflexibility in the war

plans. For example, in his first annual foreign policy report,

which was prepared by Kissinger's staff, Nixon questioned the

lack of flexibility in nuclear war plans: "Should a president,

in the event of a nuclear attack, be left with the single option

of ordering the mass destruction of enemy civilians in the face

of the certainty that it would be followed by the mass slaughter

of Americans?" (Note 10) That concern may

have encouraged Laird to support a SIOP review, but he also had

his own doubts whether "some of the President's advisors"

properly understood the relations between the SIOP objectives

and various important criteria used for planning levels of strategic

forces. To clarify those relationships and to assess the impact

of possible changes in force levels on U.S. capability to fight

a nuclear war, in August 1970 Laird directed the Joint Chiefs

to prepare, with the assistance of Assistant Secretary of Defense

for Systems Analysis Gardiner Tucker, a "detailed, comprehensive,

and quantitative analysis" of the SIOP. By the spring of

the following year, the Chiefs had completed the study. This heavily-

excised version--even the substance of Laird's directive is withheld,

despite the earlier release of the August 15, 1970 memorandum--typifies

how security reviewers treat documents with SIOP information.

It is worth noting that the DPRC's assessment of the SIOP (see

document 4, at pp. 29-30) drew heavily on the conclusions of this

JCS study.

Document

16: "The Use of Ad Hoc Groups in DOD," n.d. [circa

spring 1973], Confidential, excerpt

Source: Library of Congress, Papers of Elliot R.

Richardson, mandatory review release

Laird initiated another high-level internal review of the war

plans in early 1972 when he asked Assistant Secretary of Defense

for Research and Engineering John S. Foster to head a panel part

of whose task was to determine whether "existing nuclear

weapons employment plans … provide the flexibility to adapt

to crisis situations." Prepared as background for newly-appointed

Secretary of Defense Elliot Richardson in early 1973, this report

on "The Use of Ad Hoc Groups in DOD" included a background

paper on the creation of the Foster Panel, also known as the NSTAP

Panel. (Note 11)

Document

17: Memorandum from Ambassador U. Alexis Johnson to Acting

Secretary of State, "DPRC Meeting - June 27, 1972,"

Secret

Source: RG 59, Department of State Records, National

Archives, Subject-Numeric Files 1970-73, Def 1 US

While the Foster Panel was working on its report, the DPRC study

on "U.S. Strategic Objectives and Force Posture" (see

document 4) provided a detailed analysis of alternative nuclear

force postures. The record of a DPRC discussion of the alternatives

in June 1972 shows that Kissinger continued to promote his interest

in what Atomic Energy Commission chairman James R. Schlesinger

called "sub-SIOP options." According to Kissinger there

"was a risk of our being paralyzed in a crisis because of

the lack of plans short of an all-out SIOP response." He

wanted nuclear planners to start "thinking through what options

could be made available to the President." Schlesinger argued

that the problem required a technical solution: U.S. ICBMs needed

a very accurate capability to strike nuclear threat targets--a

"hard-target kill capability"--if limited nuclear strikes

were to be possible. What Schlesinger had in mind was the concept

of the M-X missile that was deployed during the 1980s.

Document

18: "HAK Talking Points DOD Strategic Targeting Study

Briefing," Thursday, July 27, 1972," Top Secret

Source: Declassification release by NSC

A month after the DPRC meeting, Kissinger learned from NSC staffer

Philip Odeen, who probably drafted this paper, that the Foster

panel had completed a report that was being reviewed by the Joint

Chiefs of Staff. In spite of an 11-year old FOIA request by the

National Security Archive, the Defense Department has not declassified

the Foster Panel's report; nevertheless, Odeen's summaries (see

also document 19 below) provide significant detail on its contents.

Looking at ways to give command authorities the widest possible

choice and to control the escalation of nuclear war, so as to

limit its destructiveness, the panel developed concepts of nuclear

options, including Major Attacks (essentially the current SIOP

options), Selective Options, and Limited Options. By exercising

limited options, Odeen argued, it might be possible to "stop

the war quickly and at a low level of destruction." If, however,

escalation could not be controlled and general nuclear war unfolded,

the panel proposed a new objective for U.S. forces: "to minimize

the enemy's residual military power and recovery capability and

not just destroy his population and industry."

Document

19: Memorandum to Dr. Kissinger from Philip Odeen, NSC Staff,

"Secretary Laird's Memo to the President Dated December 26,

1972 Proposing Changes in US Strategic Policy," 5 January

1973, Top Secret, excerpts

Source: Declassification release by NSC

Later in the year, with the Foster panel's report complete, Odeen

filled Kissinger in on its status and Secretary Laird's interest

in quick NSC-level approval of new strategic guidance based on

the panel's analysis. Laird was leaving the Pentagon and wanted

to see closure on nuclear policy before he left office. Odeen

was sympathetic but pointed to "important gaps and major

unresolved issues" such as the lack of detail in the analysis

of limited and regional nuclear options and the extent to "which

we should buy forces to support our [nuclear] employment policy."

Nevertheless, Odeen saw value in timely action because it meant

an "unprecedented opportunity to develop an overall policy

for a national security issue which for too long has been out

of the President's control."

Document

20: Memorandum for the Record, "SIOP Expansion Studies,"

by Eric E. Anschutz, Science and Technology Bureau, Arms Control

and Disarmament Agency, April 20, 1973, Top Secret

Source: FOIA request to State Department

While the Pentagon and the National Security Council were working

on studies responsive to Nixon and Kissinger's wish for options,

officers at SAC headquarters had been conducting studies on their

own account. (How much the JSTPS knew about the policy review

at the NSC and the Pentagon remains to be learned.) During an

ACDA staffer's visit to Offutt AFB, CINCSAC John C. Meyer discussed

some of the attack options that were under review for "illustrative

purposes." Meyer explained that actually designing limited

options would require a Presidential directive and that the work

would "take some time." He was also doubtful that the

Soviets would see "as limited" any attack "exceeding

a few missiles … particularly during a crisis."

Document

21: Memorandum from Secretary of Defense James Schlesinger

to Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs [Henry

Kissinger], 13 July 1973, enclosing "NSSM 169 Summary Report,"

8 June 1973, Top Secret

Source: declassification release by NSC

In his January 1973 memorandum to Kissinger, Odeen had recommended

an interagency review, chaired by the NSC staff, to "review,

revise and complete the [nuclear] employment policy and overall

strategic policy guidance." As it turned out, however, John

S. Foster, not an NSC staffer, chaired the interagency review

of U.S. nuclear policy that Kissinger requested under NSSM 169

in February 1973. By the time that study was finished, Elliot

Richardson had served his limited tenure as Secretary of Defense

(becoming Attorney General as the Watergate scandal developed)

and James R. Schlesinger had taken over from Richardson. Schlesinger

forwarded the NSSM 169 report with enthusiasm; as he wrote to

Kissinger, the study provided an "excellent basis" for

consideration by NSC. While the study brought out some problems,

such as whether escalation control was possible once nuclear weapons

were used, on the whole it found "desirable and feasible"

a new nuclear strategy based on concepts of a "greater range

of … attack options," escalation control, and "targeting

in large-scale retaliation those political, economic, and military

targets critical to the enemy's post-war power and recovery."

Document

22: Minutes, Verification Panel Meeting, "Nuclear Policy

(NSSM 169)," August 9, 1973, with cover memorandum from Jeanne

W. Davis to Kissinger, August 15, 1973, Top Secret

Source: NPMP, National Security Council Institutional

Files, box 108, folder: Verification Panel Originals 3-15-72 to

6-4-72 (3 of 5)

Some weeks after the completion of the NSSM 169 study, Kissinger

met with the NSC's Verification Panel to discuss the preparation

of a National Security Decision Memorandum (NSDM) instructing

the Pentagon to develop the "different options that the President

could absorb before a crisis develops and he is called upon to

make a decision." Worried that the options might be needed

someday, Kissinger explained that: "my nightmare is that

with the growth of Soviet power and with our domestic problems,

someone might decide to take a run at us." Kissinger, however,

did not want military planners to wait for Nixon to sign an NSDM

before they started developing options: "The JCS should start

planning as though the NSDM were approved." Expanding the

SIOP options would not be a quick process; according to Joint

Staff director General Weinel, it would take up to two years partly

because there were so many uncertainties, such as ascertaining

which targets had to be destroyed to "do the most damage."

How the Soviets would react was, for some, another element of

uncertainty. While Kissinger believed that the Soviets "will

be looking for excuses not to escalate," DCI William Colby

observed that they "could get into [escalation] by misunderstanding

or by a misguessing of indications." A reference to target

categories in the PRC (see page 3) apparently disturbed Kissinger

(who was then trying to develop a strategic alliance with Beijing

against Moscow) and prompted him to ask General Welch: "What

are you talking about? Is this on paper?"

Document

23: Memorandum, Winston Lord, Director, Planning and Coordination

Staff, Council, Department of State, to Secretary of State Kissinger,

"NSSM 169-Nuclear Weapons Policy," December 3, 1973,"

Top Secret, excised copy

Source: FOIA request to State Department

Not all in the government agreed with Kissinger on the merits

of limited nuclear options. One of Kissinger's close advisers,

Winston Lord, signed off on a paper prepared by several members

of the Planning and Coordination Staff that took exception to

the new thinking. While no one quarreled with the merits of flexibility,

the Staff worried about some of the implications of the concept

of "controlled nuclear escalation," including a "possible

adverse impact on deterrence, overreliance on nuclear forces,

and overconfidence in the applicability of nuclear escalation

in a wide variety of situations." The arguments did not persuade

Kissinger, who scrawled: "Good paper though I disagree with

much of it."

Documents

24 a-b: NSDM 242

Source: NSC declassification releases

- Document

24a:

Henry Kissinger to President Nixon, "Nuclear Policy,"

January 7, 1974," Top Secret

- Document

24b: National Security Decision Memorandum 242, "Policy

for Planning the Employment of Nuclear Weapons," January

17, 1974, Top Secret

With the Arab-Israeli war, among other problems, intervening,

it took some months before Kissinger was ready to present Nixon

with a draft NSDM designed to facilitate the development of a

"broad range of limited options aimed at terminating war

on terms acceptable to the U.S. at the lowest levels of conflict

feasible." The major SIOP attack options would be available

when escalation could not be controlled but Kissinger claimed

that the goals had shifted: instead of the "wholesale destruction

of Soviet military forces, people, and industry," the options

aimed at "inhibiting the early return of the Soviet Union

to major power status by systematic attacks on Soviet military,

economic, and political structures." If there was any meaningful

distinction between destroying "people", on the one

hand, and "economic" or "political structures"

on the other, Kissinger did not clarify it. In any event, he presented

Nixon with a decision memorandum which was signed ten days later,

setting in motion the complex and difficult process of trying

to expand the nuclear war options available to the White House.

Preoccupied with his own political survival, Nixon was unlikely

to have much interest in the follow-up to NSDM 242.

Document

25: Office of Secretary of Defense, "Policy Guidance

for the Employment of Nuclear Weapons," 3 April 1974, with

enclosure from Major Gen. John A. Wickham to General Scowcroft,

10 April 1974, Top Secret

Source: NPMP, NSCIF, box 343, folder: NSDM 242

[2 of 2]

Only a few months after the promulgation of NSDM 242, Secretary

of Defense James Schlesinger signed off on guidelines that came

to be known as "NUWEP" (nuclear weapons employment policy).

In keeping with the Foster panel report and the NSSM 169 study,

NUWEP tasked the military high command to develop strategic plans

based on concepts of deterrence and escalation control. Developing

the concepts endorsed by the Foster panel, NUWEP called for, and

set requirements for, Major and Selected Attack Options, Regional

Nuclear Options and Limited Nuclear Options. A key goal of Major

Attack Options was the destruction of "selected economic

and military resources of the enemy critical to post-war recovery,"

including political and military leadership targets. With respect

to economic recovery targets, NUWEP called for inflicting "moderate

damage on facilities comprising approximately 70% of [the Soviet

or Chinese] war-supporting economic base." The "nuclear

offensive capabilities of the enemy" remained a key targeting

objective. In keeping with previous targeting guidance, NUWEP

allowed for nuclear strikes under varying conditions of initiation,

e.g., strategic warning/preemption and tactical warning of attack/retaliation.

While providing detailed guidance for the major and selected options,

NUWEP discussed Limited Nuclear Options in only general terms,

perhaps reflecting the difficulty of creating plausible and realistic

options. To regulate the destructiveness of nuclear attacks, NUWEP

guidance also set parameters for Damage Expectancy (DE). DE could

be as high as 90% (and higher for some attacks) which meant that

some targets would require multiple attacks to assure their destruction.

Based on assumptions about blast damage, the DE criteria did not

take into account the destruction caused by fire, one of the routine

effects of nuclear bursts in urban areas. (Note

12)

NUWEP guided the creation of SIOP-5, which went into effect in

early 1976. By the end of the decade, however, the Carter administration

had produced new targeting guidance that downgraded the complex

task of destroying economic recovery targets. (Note

13)

Document

26: Central Intelligence Agency, "Soviet and PRC Reactions

to US Nuclear Weapons Employment Policy," 1 August 1974,

with memo from DCI William Colby attached, Top Secret, excised

copy

Source: Freedom of Information release

NSDM-242 directed the DCI to prepare a report assessing Soviet

and Chinese reactions to the U.S.'s new nuclear policies. The

CIA report, directed by National Intelligence Officer Fritz Ermarth,

suggested the uncertain state of knowledge about Soviet thinking

on limited strategic options and the limited possibilities for

controlled escalation. The Ermarth study found that the Soviets

were likely to develop capabilities for "some kinds of limited

nuclear operations," e.g. in the European theater or in a

regional conflict with China. While Soviet planning was likely

to continue to emphasize "massive strikes" in both regional

and intercontinental military operations, Ermarth believed that

over time the Soviets "will enhance their inherent capabilities

for limited nuclear operations … regardless of [their] views

about the feasibility of selective use options." Nevertheless,

the judgment that the Soviets were "less likely to adapt

limited use concepts for intercontinental nuclear operations"

suggested the risks of assuming that the Soviets would find "excuses"

not to escalate. As for the PRC, the Ermarth study surmised that

Beijing was likely to have an interest in the "restrained"

use of nuclear weapons because the leadership recognized "the

catastrophic consequences for them" of an "unlimited

nuclear exchange." While China's "modest inventory"

of nuclear forces could facilitate the creation of Limited Nuclear

Options, no evidence of Chinese interest in "selected operations"

was available.

Notes

1. Statement by Henry Kissinger, 9 August 1973; see document

22.

2. For documents on the first SIOP as well as references

to the published literature on the war plan, see "The Creation

of SIOP-62: More Evidence on the Origins of Overkill," National

Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 130, at https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB130/press.htm.

3. For early Cold War nuclear planning and the

creation of SIOP-62, see David Alan Rosenberg, "The Origins

of Overkill: Nuclear Weapons and American Strategy, 1945-1960,"

in Steven Miller, ed., Strategy and Nuclear Deterrence

(Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984), pp. 113-182.

4. For the origins of counterforce nuclear strategy,

see Fred Kaplan, Wizards of Armageddon (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1983) as well as the discussion in Rosenberg,

"Origins of Overkill." For the real limits to the capabilities

of SIOP counterforce attacks to spare civilian populations as well

as more detail on the evolution of the plan, see Matthew G. McKinzie,

Thomas B. Cochran, Robert S. Norris, and William M. Arkin, The

U.S. Nuclear War Plan: A Time for Change (Washington, D.C.:

Natural Resources Defense Council, 2001).

5. Raymond Garthoff, Détente and Confrontation:

American-Soviet Relations from Nixon to Reagan, 2nd edition

(Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution, 1994), 466.

6. Additional information on SIOP developments

will appear in William Burr, "'Is This the Best They Can Do?,'

Henry Kissinger and the Quest for Limited Nuclear Options, 1969-1975,"

Vojtech Mastny, Andreas Wegner, and Sven S. Holtsmark, eds., War

Plans and Alliances in the Cold War (London: Routledge, 2006).

7. According to Kaplan, Wizards of Armageddon,

at p. 269, 1960 estimates for a preemptive attack by all SIOP forces

on the Soviet Union and China were 285 million fatalities.

8. Hans Kristensen, The Matrix of Deterrence:

U.S. Strategic Command Force Structure Studies (Berkeley: Nautilus

Institute, 2001), at http://www.nukestrat.com/pubs/matrix.pdf

9. Kaplan, Wizards of Armageddon, 356-360.

10. "First Annual Report to the Congress

on U.S. Foreign Policy for the 1970s," February 18, 1970, Public

Papers of the President of the United States, Richard Nixon, Containing

the Public Messages, Speeches, and Statements of the President,

1970 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1971),

173. For later statements along the same lines, see "Second

Annual Report to Congress on U.S. Foreign Policy," February

25, 1971, Public Papers of the President of the United States,

Richard Nixon, Containing the Public Messages, Speeches, and Statements

of the President, 1971 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing

Office, 1972), 310, and See "Third Annual Report to the Congress

on United States Foreign Policy," February 9, 1972, Public

Papers of the President of the United States, Richard Nixon, Containing

the Public Messages, Speeches, and Statements of the President,

1972 (Washington: D.C., Government Printing Office, 1974),

307.

11. For a comprehensive study of the Foster Panel,

based largely on interviews, see Terry Terriff, The Nixon Administration

and the Making of U.S. Nuclear Strategy (Ithaca: Cornell University

Press, 1995).

12. See Lynn Eden, Whole World on Fire: Knowledge,

and Nuclear Weapons Devastation (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University

Press, 2004).

13. For useful background on NUWEP and changes

in targeting policy during the mid-to-late 1970s, see Desmond Ball,

"Development of the SIOP, 1960-1983," in Desmond Ball

and Jeffrey Richelson, eds., Strategic Nuclear Targeting

(Ithaca, Cornell University Press, 1986), pp. 70-79.

|