![[Previous]](images/prev.gif)

![[Next]](images/next.gif)

Plantation Bell at Thornhill plantation, Greene

County,

Alabama

Plantation Bell at Thornhill plantation, Greene

County,

Alabama

The slave houses looked like a small town and there was grist mills for corn, cotton gin, shoe shops, tanning yards, and lots of looms for weaving cloth. Most of the slaves cooked at their own houses that they called shacks. . . . There was a jail on the place for to put slaves in. . .

-- Henry James Trentham, a former slave describing a plantation near Camden, South Carolina

Plantations were complex places. They consisted of fields, pastures, gardens, work spaces, and numerous buildings. They were distinctive signs of southern agriculture and ultimately became prime markers of regional identity. Designed to be vast growing "machines" that produced a single crop for export -- tons of cotton, rice, sugar, or tobacco -- plantations are best understood as cultural landscapes, as human environments inscribed with the competing cultural scripts of their owners and the African Americans who were forced to work there. Successful cultivation of a crop required an array of structures including barns, stables, sheds, storehouses, and different types of production machinery. Sets of quarters for slaves were a prominent feature of any planation estate. The yard adjacent to the planter's house by itself resembled a small plantation. Here were located a range of different outbuildings including, at the very least: a kitchen, well, dairy, ice house, smokehouse, laundry, and quarters for house servants. It is no wonder then that both enslaved occupants and visitors said that plantations resembled small towns. They did.

These structures constituted the portion of Green Hill plantation designated as "Upper Town," the section of the estate that, along with the main house, was positioned on a high bluff overlooking the Staunton River.

By 1864 Samuel Pannill, owner of Green Hill, had amassed an estate containing almost five thousand acres. Only the portion of his holdings near his residence are depicted here.

Eighteen structures once stood in the "Upper Town" section of Green Hill. This selection of surviving buildings demonstrates the range in size, construction, and function of the buildings regarded as necessary to a planter's household.

I also found that on this plantation, it required more than one building to make a family residence and that, instead of having all the necessary apartments under one roof as at the North, there were nearly as many roofs as rooms.

-- Emily Burke, a school mistress from New Hampshire describing a plantation estate in Georgia

This type of one-room log building represents the most common form of slave housing found on plantations, although this particular cabin is more solidly constructed than most.

Two-unit log houses, basically two one-room houses that share a single chimney, were intended to shelter two separate families.

Slave Quarter at the E. Sterling Robertson,

Jr. ranch, Bell County,

Texas (7.3 - 7.4)

Slave Quarter at the E. Sterling Robertson,

Jr. ranch, Bell County,

Texas (7.3 - 7.4)

Built about 1860, this structure seems from the outside to have a unique design. However, the building consisted of a common quarters type, the two-unit house, repeated three times under one roof. Slave quarters intended for more than one or two families were more typical of Caribbean plantations.

Outbuildings, intended to serve the needs of the Big House, were often set out in a row at the edge of the service yard. In addition to sheltering particular tasks, they also marked the limits of the domain in which house servants were expected to work. Beyond, lay the territory of field slaves.

These two buildings, a blacksmith shop in the foreground and a small storage crib behind it, were intended for agricultural purposes. Slave artisans often recalled with pride and satisfaction the work they performed in such places.

The Gaillard [plantation] quarters was a little town laid out with streets wide enough for a wagon to pass through. Houses was on each side of the street. A well and church was in the center of the town. There was a gin-house, barns, stables, cowpen and a big bell on top of a high pole at the barn gate.

-- Ned Walker, former slave on a plantation in Fairfield County, South Carolina

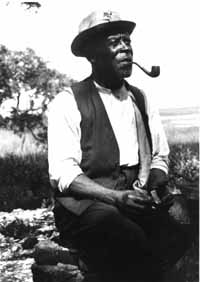

Ben Horry, former slave on Brookgreen

plantation, Georgetown

County, South Carolina (8.1)

Ben Horry, former slave on Brookgreen

plantation, Georgetown

County, South Carolina (8.1)

Barn at Bremo plantation, Fluvanna County,

Virginia (8.4)

Barn at Bremo plantation, Fluvanna County,

Virginia (8.4)

Completed in 1817, this barn is one of the largest and most substantially constructed farm buildings in Virginia. Designed as a stable for horses, the barn was also intended to be seen as proof of the success of the reform-minded methods employed by the plantation's owner John Hartwell Cocke.

Next section of The Cultural Landscape of the Plantation Exhibition

Table of contents for The Cultural Landscape of the Plantation Exhibition